|

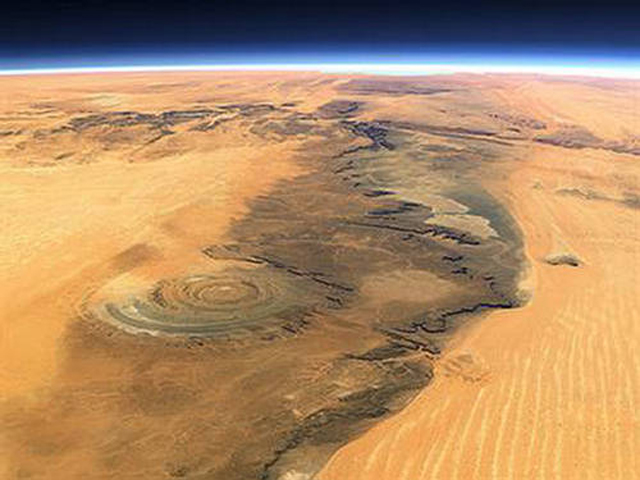

| Europe/Africa on the left |

Atlantis: What Do We Really Know?

Atlantis is one of those words that everybody, everywhere has heard or seen, and not just because it is a casino in the Bahamas or a recent

Disney movie. If you asked someone where the United Nations was founded, or when the dinosaurs died out (both are trick questions, incidentally), you most likely would get a blank look or a wrong answer. Say the word "Atlantis," though, and you will see instant recognition in your interlocutor's face with an even quicker opinion. However, for such a well-known name, amazingly little is known about it.

|

| A low-key depiction |

Plato

Plato was one in a series of Greek philosophers whose names also are commonly known. Socrates taught Plato, Plato taught Aristotle, and Aristotle taught Alexander the Great. Each man added something special to the river of knowledge that flowed from one to the next. Plato, who lived from roughly 423-347 B.C., was quite possibly the brightest of them all. Since these fellows laid the foundation of Western philosophy and science, that is saying quite a lot.

|

| Atlantis had ringed canals |

Scholars were different in the old days: they didn't sit behind a desk or simply write, write, write. Instead, they went out and experienced the world. When he wasn't busy putting down his philosophy in the Socratic Dialogues, Plato found time to travel extensively. That was quite unusual in those days - it wasn't as if he could just go to the airport and catch a flight. Travel by sea was dangerous, there were pirates and storms and enemies and dangerous natural phenomena. Plato managed to wander around quite a bit. It is believed that he visited Italy, Sicily, Cyrene in North Africa, and Egypt. Not long before he died at a wedding feast, he spit out a couple of throwaway dialogues called "Timaeus and Critias.

|

| Atlantis in Spain? |

Timaeus and Critias

The dialogues "Timaeus" and "Critias" were published in 360 B.C., about a dozen years before Plato's death. Something prevented Plato from finishing "Critias," which was somewhat odd because he had plenty of time to complete the manuscript. The first time that the name "Atlantis" appeared in Plato was this passage from "Timaeus":

For it is related in our records how once upon a time your State stayed the course of a mighty host, which, starting from a distant point in the Atlantic ocean, was insolently advancing to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot. For the ocean there was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, 'the pillars of Heracles,' there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travelers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean. For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent. Now in this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvelous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent.

Plato used the Socratic Dialogue method to make his points. It is a marvelous rhetorical technique still taught to lawyers today, and involves asking questions in order to get desired responses and make an argument. In "Timaeus" and "Critias," Plato used four characters to make his arguments for him: Critias, Timaeus, Socrates and Hermocrates. We will never know for certain, but it is highly likely that Plato was purely putting his own words into these characters' mouths. Having different people express different sides of an argument made what otherwise would have been a dull academic disquisition into a back-and-forth that still holds the attention of readers 2400 years later.

|

| Drawing of Atlantis |

Plato assigned all the mentions of Atlantis to Critias. This character supposedly was a politician, though Critias knows an awful lot about history for the average ancient politician about something for which no known record survives. In response to a request from Socrates of an example of a "perfect society," Critias comes up with a description of the place called "Atlantis."

|

| Atlantis in the Atlantic |

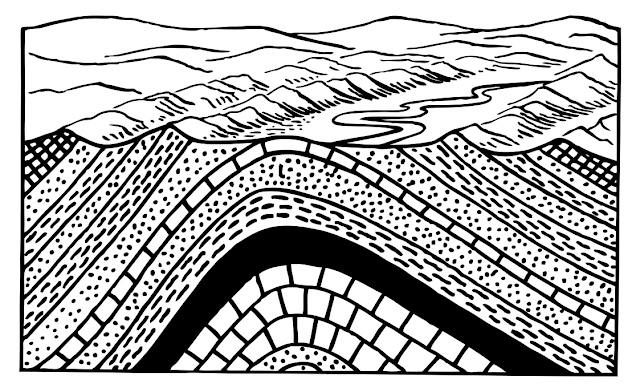

Atlantis, according to Critias, was a huge island owned by the sea god, Poseidon. Atlantis was described as larger than Asia Minor and ancient Libya combined, which to the Ancients meant it was enormous. He said that the Egyptians knew about Atlantis, and they claimed it had mountains to the north and along the coast, with a great plain extending to the south. Poseidon's son, Atlas, inherited Atlantis and the ocean in which it lay, while Atlas' twin owned a little portion of it near the well-known Pillars of Hercules. Poseidon also had four other sets of twins, who also had small portions to call their own, meaning the island was divided into territories.

|

| Is this what Atlantis looked like? |

Poseidon lived on the island with his wife, Cleito. He built himself a grand palace and enclosed it within three circular sets of moats. There were bridges spanning the moats, and a canal to the sea, with canals also allowing ships passage along the road to Poseidon's palace. The city was an armed camp, with soldiers everywhere attending to gates and towers.

|

| Artist's rendering of Plato's description |

Critias said that 9,000 years before (which would have been roughly the period of the last Ice Age), Atlantis had engaged in a war which brought it possession of North Africa, including Egypt, and Europe as far as Italy. The Atlanteans were not nice people and enslaved the conquered inhabitants. The Athenians led an uprising, which was successful. Greater problems, though, awaited the Atlanteans. The entire island of Atlantis disappeared in a single day:

But at a later time there occurred portentous earthquakes and floods, and one grievous day and night befell them, when the whole body of your warriors was swallowed up by the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner was swallowed up by the sea and vanished; wherefore also the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal mud which the island created as it settled down.

That, believe it or not, is the entire known history of Atlantis. So, where did Plato get the idea for the island, or even the name? Well, surprisingly, there was a possible source for the name, in a pedantic work by someone named Hellanicus of Lesbos (Lesbos being a well-known Greek island). Hellanicus simply listed the descendants of Atlas, but he almost certainly was basing his work on earlier source that now is lost - which suggests that "Atlantis" was an accepted place name at that time.

Crantor

Plato taught Xenocrates, who in turn taught Crantor. As part of his studies, Crantor commented on Plato's "Timaeus," which at that time would have been cutting edge research and perhaps controversial. This was actual research not just a desk exercise as might be the case today. We don't have Crantor's actual critique, but it did survive intact throughout the Roman Empire (and thus a copy may, perhaps, still lie in one of those unexcavated villas in Pompeii or elsewhere in the old Roman Empire). The Roman Empire came and went, and then a philosopher named Proclus mentions Crantor's work:

As for the whole of this account of the Atlanteans, some say that it is unadorned history, such as Crantor, the first commentator on Plato. Crantor also says that Plato's contemporaries used to criticize him jokingly for not being the inventor of his Republic but copying the institutions of the Egyptians. Plato took these critics seriously enough to assign to the Egyptians this story about the Athenians and Atlanteans, so as to make them say that the Athenians really once lived according to that system. Crantor adds, that this is testified by the prophets of the Egyptians, who assert that these particulars [which are narrated by Plato] are written on pillars which are still preserved

That last sentence is the crucial one. Crantor apparently had visited Egypt to check up on Plato's account, and, according to this fellow Proclus who was reading what Crantor wrote, Crantor found solid proof of Atlantis there.

|

| A possible location in the Pacific |

Proclus

When we come to Proclus, who was writing about a thousand years after Plato, we are getting a bit far from the original source. However, according to Plato (speaking as Critias), Atlantis had disappeared a good ten thousand years before Proclus, so it's all relative. What is certain is that Proclus had access to books that we do not, and not just Crantor's examination of Plato. As Proclus writes:

That an island of such nature and size once existed is evident from what is said by certain authors who investigated the things around the outer sea. For according to them, there were seven islands in that sea in their time, sacred to Persephone, and also three others of enormous size, one of which was sacred to Hades, another to Ammon, and another one between them to Poseidon, the extent of which was a thousand stadia [200 km]; and the inhabitants of it—they add—preserved the remembrance from their ancestors of the immeasurably large island of Atlantis which had really existed there and which for many ages had reigned over all islands in the Atlantic sea and which itself had like-wise been sacred to Poseidon. Now these things Marcellus has written in his Aethiopica"

As can be seen here, Proclus actually names the author of one of those books that we don't have, someone named Marcellus. "Aethiopica" is a reference to Africa, and if Marcellus discusses it in a book on Africa, that is a hint that Marcellus' sources showed Atlantis as lying in some relation to that continent - not Europe or the Americas.

|

| Donnelly's map |

There may be some circumstantial corroboration for the existence of Atlantis from other sources, but it is very sketchy. The Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus (is this the "Marcellus" of Proclus?), also referencing a work now lost, mentions that the Druids of Gaul claimed partial ancestry from an unidentified island. The people of the Basque region of Spain, which seems a likely spot for refugees from an Atlantic island, are well known throughout history (including today) as having had their own language and culture, distinct from any other in Europe. When you see the recurrent headlines about "Basque separatists," you might just be learning of the current struggles of the descendants of the Atlanteans.

Modern Scholarship

There is all sorts of nonsense masquerading as science regarding Atlantis that was written for sensationalistic purposes over the past few hundred years. An American politician, Ignatius L. Donnelly, wrote an 1882 book about Atlantis called "Atlantis: The Antediluvian World" which was simply conjecture and hypothesis. Nothing wrong with that, nothing at all, but he had nothing more to go on beyond what we have today, namely, Plato and the others. Edgar Cayce, a well-known and respected American psychic, made all sorts of comments about Atlantis which, wonderful healer and philosopher that he was, cannot be taken at face value.

|

| The Atlantis Massif and Fracture Zone |

That doesn't mean that nothing new ever can be known about Atlantis. If Atlantis existed, there is evidence, and that evidence can be found. The only argument that suggests nothing new can ever be known about Atlantis is the one that goes like this: Plato was merely a rhetorician and philosopher, not a historian, and he made up his entire story of Atlantis. Scholars love to say that anyone who thinks that there ever was a place named "Atlantis" simply "misunderstands" Plato. There is all sorts of textual and interpretative rationale for this, but it is odd that Plato would give such precise coordinates for an imaginary place. It also negates the tantalizing reference to Atlantis by Hellanicus of Lesbos - which proves that the place was not completely made up by Plato. Still, the Atlantis deniers have a very valid position that can only be disproven by the actual discovery of an ancient place that resembles Plato's description.

|

| A representation of a possible site |

Santorini/Thera

Fads about where Atlantis may lie come and go. Donnelly, the one who wrote "the book" about Atlantis, was positive it was in the middle of the Atlantic, but nobody really believes that any more (though there is no absolute proof to the contrary). A theory in vogue in the 1960s, which still retains some support by tourist guides, is that Atlantis lay on the ancient island of Thera (renamed Santorini in modern times). What is particularly convenient about the Thera theory is that the island mysteriously blew up during ancient times. Visitors to the island quickly become entranced by the black volcanic beaches, the white cliffside dwellings, and the excavations of ancient towns frozen in time by the lava that covered them during the island's demise. The main problem with the Thera theory, and unfortunately it is a big one, is that Thera was extremely well known to Plato and his cronies. It was not nearly as large as Plato described, and there is nothing particularly dramatic about Thera in any other ancient source (besides the fact that it blew up). If Thera had been Atlantis, Plato would not have babbled on about the Pillars of Hercules, which also were very well known then. Instead, he simply would have said, "Atlantis, which was on Thera, which blew up." He was trying to be scholarly, not mysterious. But he never mentioned Thera, and everything else in his dialogues (again, besides Thera's fate) is completely contrary to the idea that Thera was Atlantis.

|

| The Spanish site |

Southern Spain

In 2011, there was exciting news: Atlantis had been discovered! An American Professor, Richard Freund, claimed to have found evidence for Atlantis in southwestern Andalusia, extremely close (practically nest to) the Pillars of Hercules mentioned by Plato. Apparently, there are marshlands in a park there which contain ruins which have some similarity to the circularity described by Plato. Since Plato also mentioned that the sea became muddy and impassable because of the demise of Atlantis, the location in a marsh was quite fortuitous. Dr. Freund theorized (or, according to his critics, speculated) that a tsunami (very much a current topic in 2011) probably wiped out Atlantis, leading to its refugees fleeing elsewhere in Europe and Africa.

|

| Geologic data of the Spanish site |

However learned Professor Freund may be, his conclusions are almost as reckless as Donnelly's were a hundred-odd years before. The Spanish are not bumpkins, and they have known about the site for a long time. They were not particularly delighted to have work they had been grinding through for years suddenly sensationalized by an American-come-lately. The southern Spain theory in fact had been put forward long before by others (Rainer W. Kuhne, Adolf Schulten), but no proof of Atlantis has been found there. The problem with Dr. Freund's theory, and again it is a big one, is that the area is crawling with researchers and scientists, and if there were ruins of Atlantis, somebody likely would have found them before, without any need to resort to speculation. But work there is ongoing, so further developments await.

|

| Satellite photograph of the Spanish site |

The mid-Atlantic

The obvious place for the location of Atlantis is somewhere in the Atlantic. Edgar Cayce said unequivocably that Atlantis lay there, with parts to be found by a specific date near Bermuda (unfortunately, the date came and went, and no Atlantis, though dates in this particular field are, shall we say, malleable). The beauty of the mid-Atlantic theory is that the Atlantic is huge, and there are many areas that have not been investigated. The presence of island such as Bermuda, the Canary Islands, the Bahamas, St. Helena and the like might identify the tops of the old Atlantean mountains. Once again, though, there is no proof, and with the intense interest in this question, every time an actual location in the Atlantic is suggested, "irrefutable" evidence immediately is adduced to rule that spot out. We are no closer to being able to say that the Atlantic hosted Atlantis than we were in Donnelly's day.

|

| Atlantis in the Atlantic? |

The Indian Ocean

One good thing about the Atlantis story is that it keeps researchers on their toes. As with the discovery of the Titanic, whoever produces tangible evidence of Atlantis will go down in history with the greats. Their name(s) in this case will be forever linked with Plato. For a scholar, there is no greater prize. It is difficult to think of a more sensational discovery than Atlantis, aside from, say, the Second Coming, a cure for cancer or a high-profile visit from intergalactic aliens.

|

| A beach in Mauritius |

Kumari Kandam is the ancient name for a submerged continent in the Indian Ocean. Surviving ancient Tamil books describe Kumari Kandam as lying off the southern coast of India. No single writer came up with the story of Kumari Kandam: instead, it was an accepted fact among many writers of the period. There is an extensive description of the place as being divided into numerous territories which is not necessarily inconsistent with Plato's account. The Indian Ocean is huge, and certainly could have housed a continent of the size described by Plato. There are many refinements about Kumari Kandam in the ancient Tamil literature, but the main points are these: it was huge; it was advanced; and it was divided into different regions. That all sounds suspiciously similar to what Plato had to say about Atlantis.

|

| Atlantis near Indonesia? |

The beauty of the Kumari Kandam theory is that actual

proof from the scientific establishment recently has been supplied for its actual existence. Kumari Kandam is no longer just a myth or a "tale." Kumari Kandam existed, and it lay precisely where the ancient sources say it did, between the southern tip of India and Mauritius, the island nation off the east coast of Africa. Proof of the type that hard-core scientists trust a lot better than some dusty old writings - sand grains on Mauritius - suggest to these scientists that this ancient continent fell into the sea, and then partially re-emerged. This is uncannily similar to some accounts (such as Edgar Cayce's) of Atlantis.

These discoveries were just announced in February 2013, so nothing is settled. This description of the findings is not meant to imply that Kumari Kandam equals Atlantis, which is extremely doubtful. The immediate major problem with the theory is that Kumari Kandam is not precisely where Plato said it would be - but even cynics have to admit that Plato was vague enough to support a location practically anywhere beyond the Pillars of Hercules. There is no evidence yet that anyone lived on this now-submerged continent, or that anyone could have due to how long ago it supposedly sank (though how did people know to write about the place if nobody ever lived there?). Think what you may about any relationship between Atlantis and Kumari Kandam, this startling discovery gives tantalizing support to people who choose to believe that we don't yet know everything about the world's oceans and what may lie beneath them - including, possibly, Atlantis.